Post #13 TETRIS in ABAQUS Part 2

- guyrushton9

- Dec 21, 2025

- 9 min read

Creating an interactive dialog box through the medium of classic gaming…

The game design requirements were laid out in Post #12. Here we shall deal with the user interface for the implementation of Tetris in ABAQUS.

The original Tetris did not have a user interface, being played on a handheld device, it had buttons on the box to control the position and orientation of the blocks. The obvious thing to do for a PC game would be to have key press capturing, as is normal for many simple games. However, this is disabled in the ABAQUS implementation of Python. Therefore, we must make do with buttons implemented on a basic dialogue box.

This drives us towards a plugin, which offers a further opportunity, to make use of the processUpdates function to provide a game loop, i.e. a loop within which the game operates until the user cancels out of it. The key aspect of game play in Tetris is that the current shape that you must stack advances at a regular rate down the play space until it either reaches the end or contacts another block. This is easily done within a conventional loop, but, as we shall see later, it is not so easy to achieve reliably in an ABAQUS plugin, which is geared to user input.

Finally, there is the question of persistence of data and access to that data for both the kernel and the GUI, for example maintaining and displaying the score. To allow both sides of the plugin to access common information we shall make use of the customData space in the model.

The User Interface

A simple dialogue box is used, as shown below. It has buttons as shown:

Move block upwards

Rotate block to the right

Rotate block to the left

Move block downwards

Advance the block as far as possible down the playing area

Start/Stop the game

Quit the plugin and clean up the working area

The first five buttons are conventional buttons. They are defined using FXButton and require a handler function, in this case a single function onButton that sorts the message IDs to determine which button was pressed. Each button increments the value of an associated keyword. This forces a pass into the update loop in processUpdates, where the changed keyword is identified and a command is sent to the kernel. Normally you would directly send the command from the handler function but in this case, we want to handle these calls within the processUpdates loop, for reasons that will become clearer later.

The last two buttons are action buttons, that is they are in the action area, and they behave slightly differently. They are tied to the dialog system’s methods for starting and stopping the dialog. The Start Game button is an added action button, with its own handler function, onStart. It could have been another conventional button. The handler’s behaviour changes depending on a status flag that is held in the start keyword.

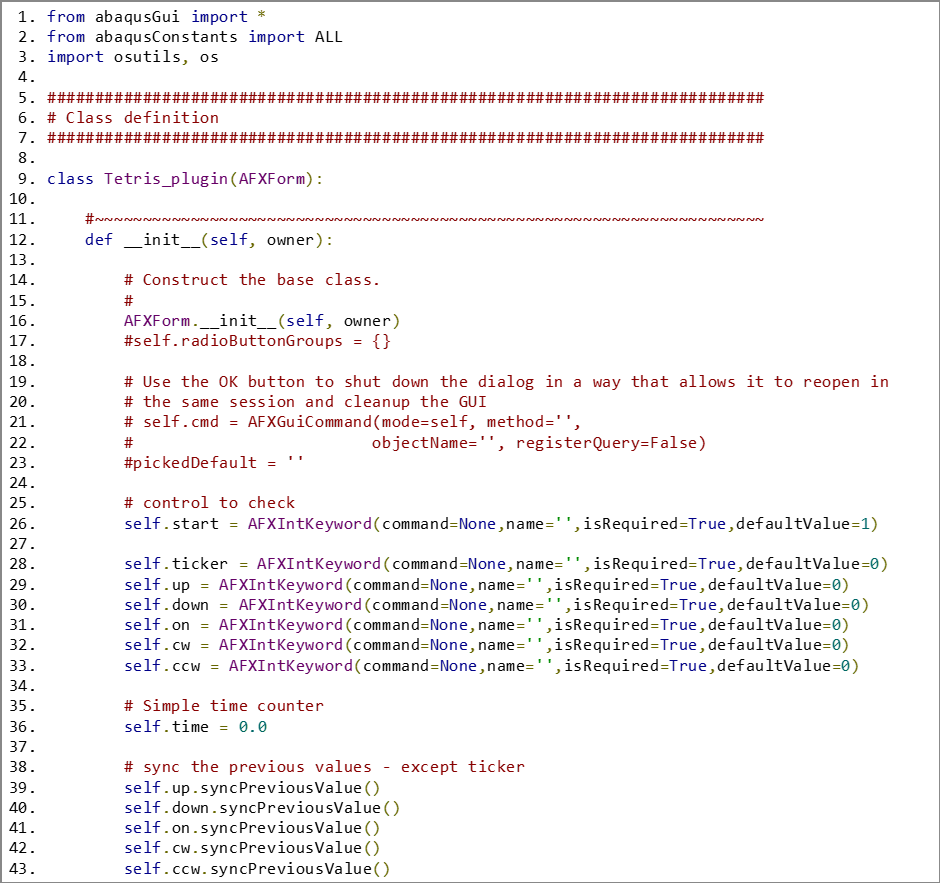

The Quit button is a relabelled OK button. This was done, rather than using a Cancel button, so that exit checks, via the doCustomChecks built in function, see the form file, could be carried out that affect the GUI. Since there is no command tied to the button only the actions contained in the doCustomChecks dialog function are carried out. The code to define the user interface is given below:

Notice the sections highlighted in yellow. The first is the message map, which must be placed right at the head of the class, where a list of message IDs is defined, one for each button in this case, including the start button. The second section is the collection of mapping macros, FXMAPFUNC, that link the message IDs to the message handling functions, in this case there are only two, onStart, which deals with the start/finish button and onButton which handles all the other button presses.

The lines highlighted in purple deal with the action buttons, the last line adds an action button for the start/stop game and ties the custom message ID_START to it, to match the macro and the message map above it.

The first purple lines relabel a default OK button, identified from its default message ID_CLICKED_OK. This is a built in button and does not need its own message handler to perform the standard responses for an OK button i.e. to launch some commands, not done in this case, and unpost the dialog in a controlled manner.

The remainder of the code builds and arranges the buttons within two column frames. Notice how the buttons are all children of the vertical frame objects and they in turn are children of the dialog object. Each button points at the target self and sends its message there, i.e. to the message map defined at the top of the class.

Button Handlers

There are two button handlers, onStart for the start/end game button and onButton to handle the block positioning buttons. As will become obvious a single function could have been used to do this, simply extending onButton, but it is a clearer separation of function and keeps the functions to a sensible length.

onStart

This function handles the added action button. Action buttons appear in the tray at the bottom of the dialog. They can be customised, as this one has in the simplest way by relabelling.

The action within the handler is defined by the value of the start keyword, which has an initial value of 1. If the start button is pressed and start ==1 then the game is initialised, including modifying the GUI by hiding the command line and message windows. A first shape is created and placed and then the game loop is enabled, by setting start to -1. Finally, the button is relabelled to show that another press will stop the game. Notice where the change in the keyword value is done. It is important to avoid overruns of the game update loop so the value change to start is after the initialisation and the value to change to finish is before the end of game actions. This will become a little clearer when we look at the processUpdates function below, where the game loop happens.

onButton

This handler deals with all of the block orientation buttons by sorting the message IDs in the function, using the SELID macro link to values in the message map, then applying actions. Ordinarily the actions would be applied directly in this function by calling sendCommand to issue instructions to the kernel as needed. Here keyword values are being changed instead. This is to ensure that button presses are captured and acted upon. Commands sent direct from here would not be synchronised with ones from processUpdates and they can be ignored. I got better results by updating the keywords and then having the actions launched from the update function triggered by a change in the keyword value.

Game Loop

To make a game loop we shall be forcing the processUpdates function to work in the opposite manner to its usual behaviour. Normally you would want this as quiet as possible. It usually operates when there is mouse movement over the dialog or user interaction with widgets that need to be updated.

In this case we need a regular, and very frequent, pass through this function to ensure not only that button presses are captured but that the blocks advance in a regular manner down the playing surface.

The section highlighted in purple below handles the orientation buttons, the button press is captured by the keyword value change, and the appropriate kernel function is called.

The section in green deals with moving the block down the track. It checks that the current time is a given amount beyond the previous advance time, held in the simple variable time. If it is the block translates one unit down the playing surface, with time being updated to the current time.

The section in grey handles end of game events. The value checked here, finish, is in the kernel customData, which can be read from the GUI. Finish is updated by kernel scripts that check the game status. This is needed because sendCommand does not have a return value which could have been used to check the game status. I did attempt a call back function at one point in the development to achieve the same result but it was unnecessarily complicated.

Finally, the green section, the beating heart of the update loop and the cause of considerable and unexpected trouble. The theory was simple. In normal loops keyword values are checked for change. When a change is found an action is taken and the keyword value is synchronised, via syncPreviousValue, which prevents a second pass through the handling function. Logically, therefore, not synchronising, should cause the loop to run very fast, repeatedly checking this section of processUpdates. This is what normally happens, and it usually causes ABAQUS to hang as the loop wraps around itself. Not today. For some reason it would only update when the mouse moved over the dialog. Not helpful. The next obvious thing to do is to synchronise the ticker value and immediately update its value to force another cycle. The same result, not moving the mouse results in the block sitting there, making the game quite easy!

So, I experimented. At some point, for reasons I am still not clear about, the high-speed looping until it failed returned. OK, so now I just put a delay in the loop, and everything is OK, right? Wrong. A delay in the kernel, inside controlLoop, just gave strange results and more crashes and a delay in the processUpdates function simply slowed everything down but also messed up the key press reading, apparently because the key presses are not looked for while the GUI is in update mode.

Through trying all these combinations, I had left the button handlers with standalone calls to the kernel, rather than updating within processUpdates and the asynchronous nature of this did not help.

Getting desperate, I put a loop within processUpdates. This did not end well. No user interaction was possible at any point.

The answer, bizarrely, was to make controlLoop an empty function, it only contains a pass statement, and to update the value of ticker, as shown. This produces a stable response and makes the update cycle continue automatically. I can only deduce that the update cycle is triggered by the completion of a kernel function, to refresh the display of data, so simply making it an empty function is enough. By having the buttons update keywords and these being checked on every pass the game updates are synchronised.

Those of you who are more familiar with coding plugins may have noticed in the source code that I have written error output and test output to stdout rather than use getAFXApp().getAFXMainWindow().writeToMessageArea(<text>) to supply comments to the message window. This is for two reasons. Firstly, I have, for purely aesthetic reasons, suppressed the message window, so you cannot see the output. Secondly, more practically, when you are developing a GUI, it is quite common for it to crash ABAQUS. At that point only the command window is left open. So, writing to the stdout will leave your bug trapping comments alive there when the main program disappears.

Mode Code

The mode or form is where the plugin keyword data is held and where the dialog starts from, it is from here that the plugin is registered and the first dialog definition is loaded. The file must always be called <name>_plugin.py and it must live in your abaqus plugins folder in your user space, together with your <name>DB.py file that defines the dialog, see above, and the kernel file that contains all the model manipulation code. It must contain the plugin registration section at the end, modified to meet your plugin's needs of course.

This example is pretty simple; there are a small number of keywords and only a single dialog is loaded. The most unusual features are:

doCustomChecks has a non-default implementation. In this instance it restores the GUI elements, which must be done from a GUI file, you cannot do this from a kernel module. It then calls a final kernel script to send the working area back to default settings.

A function call has been added to the kernelInitString in the plugin registration. Multiple imports and calls can be added to this string, depending on your file structure and initialisation requirements. In this case I wanted all the stored data to be preset.

Conclusion

This is an unusual dialog box in that user interaction and high-speed updates are required and the normal processUpdates operation has been deliberately inverted.

The source code for this whole project is available to download using the button at the top - look for blog post #12.

Comments