Post #10 Beginners File IO

- guyrushton9

- Nov 10, 2025

- 5 min read

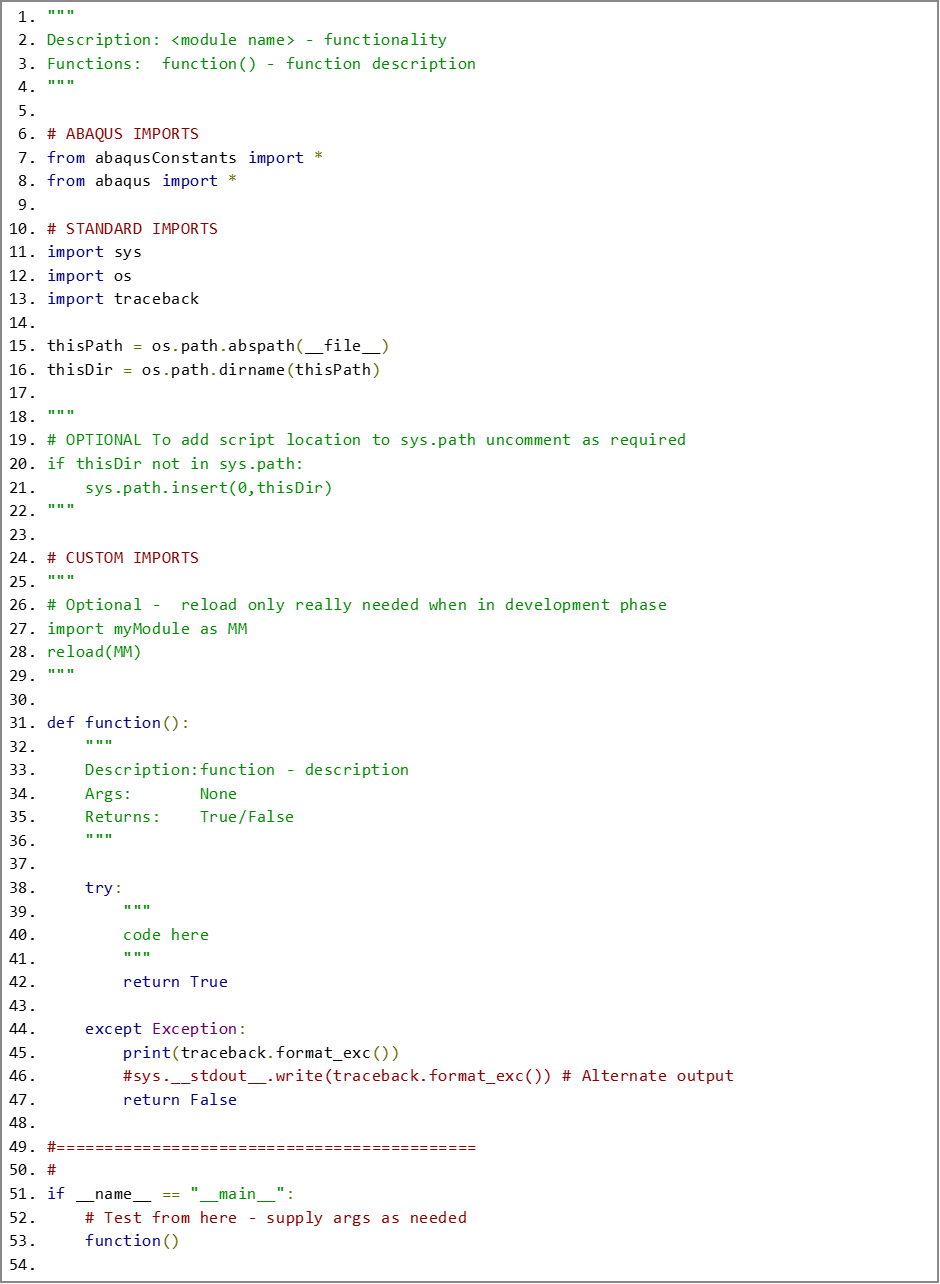

For this week’s blog post a very unglamorous subject for the scripting beginner: reading and writing basic text files to and from ABAQUS and formatting the data so that appears in tabular form for use elsewhere. Not difficult, but a potential source of headaches for the beginner. There is no difference in the file operations between using Python in the ABAQUS environment and regular Python. Once you have the basics of file I/O then you can start to interrogate your models and your results to extract useful data.

The simplest trick of all is printing output to the message area in a regular format that can simply be copied and pasted into whatever document you are working on that needs it. This example simply shows my lack of curiosity about the Python language, beyond the limits of Python 2.x for ABAQUS. Until recently I assembled lines of text, with tabs and printed whole lines. Stupid. The answer is a lot easier in Python 3.x, and can be made available in Python 2.7 as shown:

The future import is needed to bring the end keyword into play, unless you are using Python3.x. It must be included at the head of the module. Now it simply prints to the message window, one element at a time, separated by a tab, without a new line until the blank print statement which produces a carriage return by default. The result is a neatly tab-delimited times table in the message window.

Basic Files

Often printing to the window is not enough, a file is needed, either as a record or for the next stage of processing in another application like Excel – though why would you when you can process your data with Python?? Python makes handling text files relatively simple but there are some things that can be made a lot easier. There are additional libraries that can really help. Typically, I avoid using extra libraries within ABAQUS because it can be a real pain getting the right versions, more on that in a future blog post. Bearing that in mind, the most vanilla file I/O operations are as follows:

Using the with syntax for opening the file should mean that the file is automatically closed on completion.

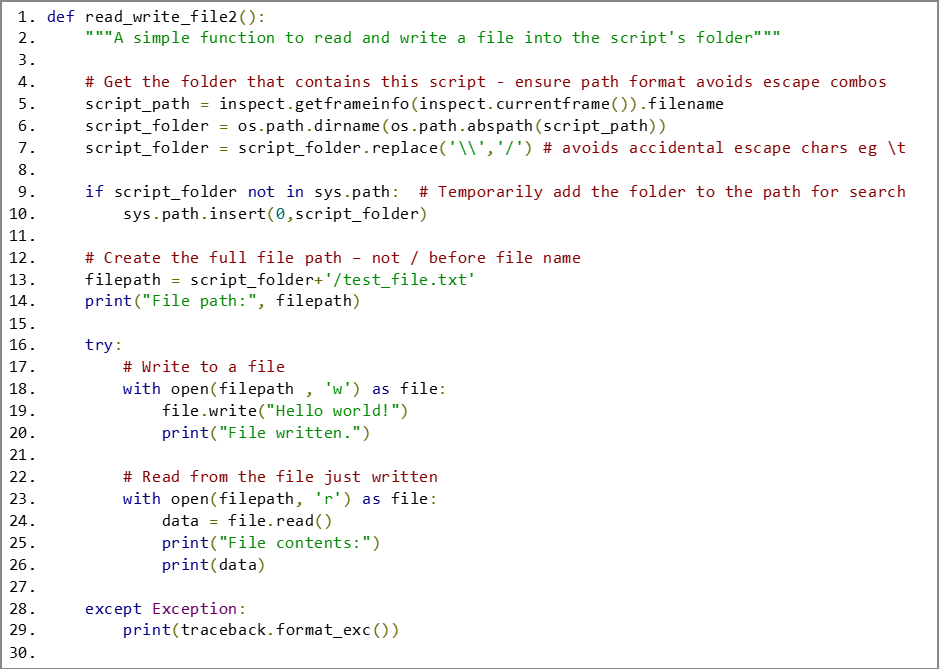

This is fine as far as it goes, except that it will dump the output file wherever your current working directory is. This may or may not be what you want. I often write plugins that need to read or write to data files that are in the same folder as the plugin. To do this is simple, you have to specify the full path of the file, including the script’s folder. You can do this manually but then you have to have the source code and edit the path. A better way is to interrogate the script to find out where it is. This is done using the inspect module as shown below:

Here the inspect function getFrameInfo returns the path of the currently executing script. The os functions split out the folder and the default file name is attached to it, note that you need to add the extra forward slash before the file name.

File Dialogs

You can obviously simply define a fixed output folder, which may be all you need, the path could be an argument to the script at run time allowing for easy changes. Effective but inelegant. File dialogs give you more power.

This next is a direct example from my book ABAQUS Scripting Springboard and is in turn a shameless copy of a worked example from Mark Hammond’s PyWin32 page on github:

Look him up, offer thanks, I certainly do. There are lots of other examples on there that you can bend to your will.

The good news is that the PyWin32 library now ships with ABAQUS so you don’t have the hassle of installing it yourself, like the bad old days. It also works with kernel scripts so there is no need to delve into writing GUIs. This example shows the Save dialog, the Open dialog is exactly the same, just change to win32gui.GetOpenFileNameW in line 56.

File Format

Mostly you will be putting out text. It may need to be formatted text. The simplest is something like a tab or comma delimited text file. You might need to include other data, for example free form text explaining what the results mean. It can be an advantage for your code not to depend on a fixed header format.

Depending on what you are writing you may find the write or writelines functions for the file object the easiest. The example that follows uses both, replicating the trick at the top of this article to create a tab delimited table of data of user determined size, preceded by an arbitrary number of header lines. The columns and rows are labelled. The whole data table, including the labels, is put inside markers to allow that table to grow and shrink freely and still be easily read by the reading routine.

There are other simple ways to do this but using markers means that the same code can read a file it created later, without having to put a header line count in. The header could be edited and updated elsewhere without affecting the table data extraction. A primitive markup like this also means that more than one table can be stored in a file and easily extracted. The result of this example is shown here:

Conclusions

Text format files will get you a long way, in storing or post-processing your results and also just being able to paste the results into a report. Consider the case that you have a report template that just needs a data table and some pictures pasted into it to complete it. More complicated file formats can be used, especially for report generation, and I shall cover examples in RTF and HTML in the future.

As always the source code for this blog can be obtained for free via the download button at the top of the post.

Comments