Post #2 More Fixing My Mistakes: Tie Constraints

- guyrushton9

- Aug 10, 2025

- 4 min read

Updated: Aug 25, 2025

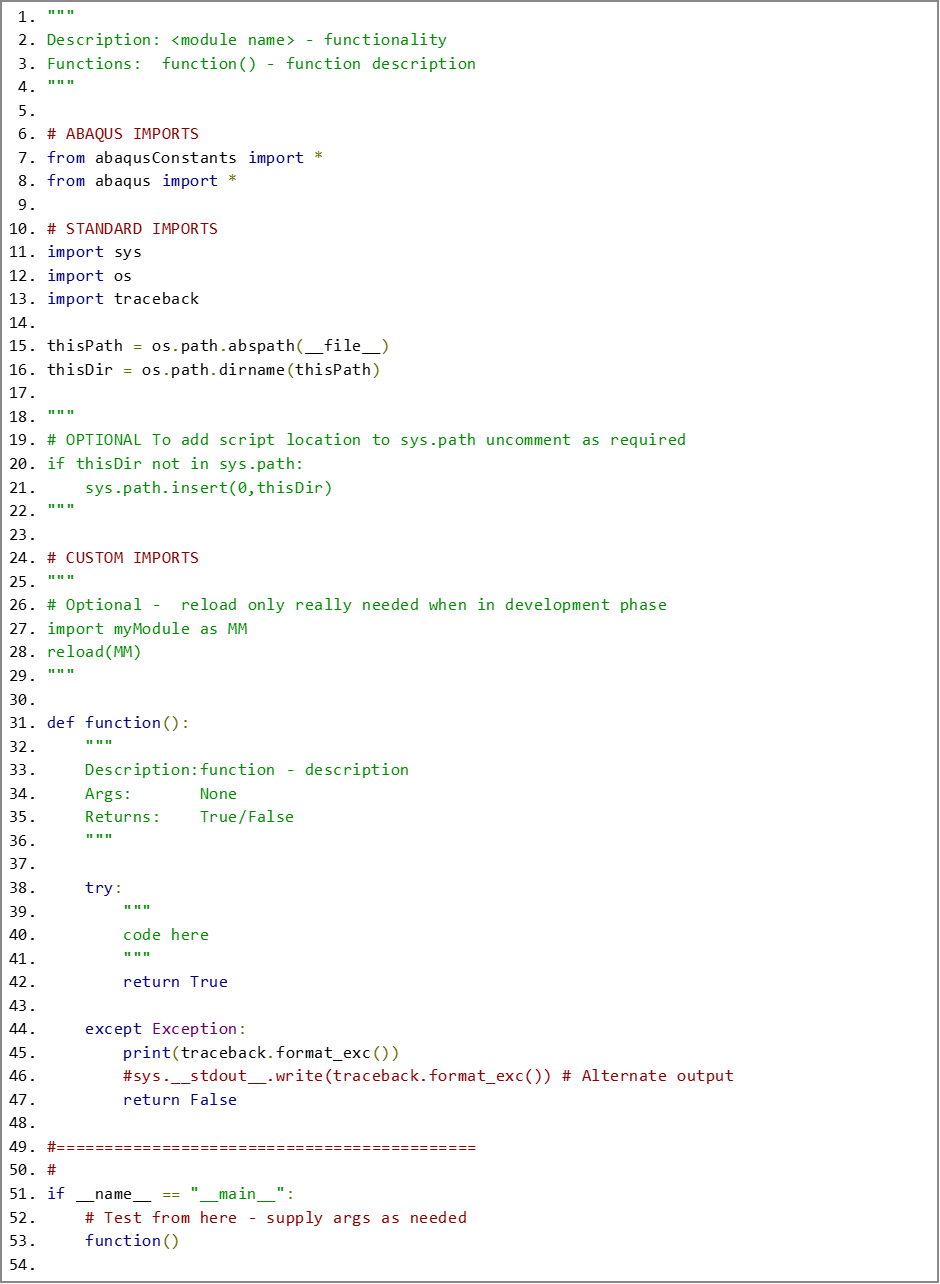

Another example of me making lemonade from life’s lemons: two scripts to help clean up a series of large models where I made some very basic errors while trying to do too many other things at the same time.

In this case I have a series of models with a lot of bolts, more than 100, modelled as solids in the assembly under analysis. Do not ask. The bolts had named surfaces, where the thread section would be tied into the mating part, and where the head contacted the mating surface. Unfortunately, due to time pressure, I did not take the precaution of naming all the contact surfaces on the compressed parts. Which piece of corner cutting came back to bite me when I copied and edited the base model a number of times and the ties became a bit scrambled, a bit like the simplified example in Figure 1. I shall be showing off a plugin to quickly name a large number of surfaces in the very near future.

Fixing this foul up across several models was going to be a time consuming and painful process with no certainty that my human frailty, boredom, meetings or lack of coffee wouldn’t cause a repeat of the mistakes. So, I reached for the scripting to provide a quick and reliable solution. Those of you who saw my earlier post about fixing these large models will remember that in that case I was able to use the macro recorder and generalise the solution very quickly. This one is a little more involved, however, with some judicious use of AI to help find the right distance sorting code it did not take too long to do.

Clean Up

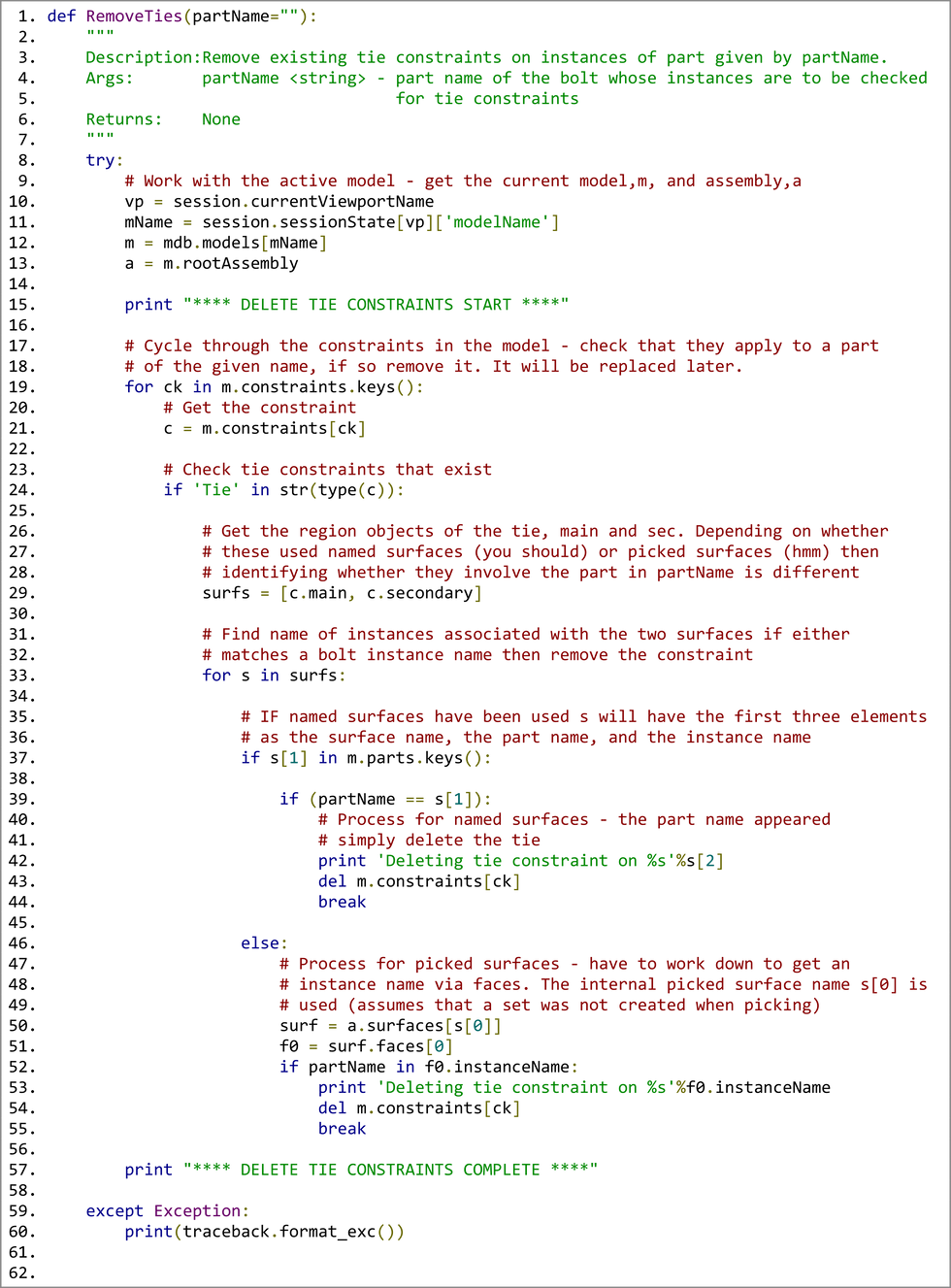

First things first, cleaning up the existing messed up tie constraints. I could work down the list by hand. Or I could use the script in Figure 2 which looks through all the constraints and removes those that are ties and that refer to the named part in either the primary or secondary surfaces.

Note - named surfaces appear in the model tree, albeit usually indicating that they are part level surfaces, which must be accessed via their instances:

mdb.models[<name>].rootAssembly.instances[<name>].surfaces[<name>]

Internal, picked, surfaces do not appear in the tree at all. If you look in the DisplayGroup manager and look for Internal Surfaces you will see a list of items of the form _PickedSurf##. These can be accessed directly from the assembly level:

mdb.models[<name>].rootAssembly.surfaces[<name>]

The script works through, checking all the constraints and deletes any that meet the selection criteria.

New Constraints

After removing the original constraints from the part instances, the next step is to replace them with correct ones using the CreateTies script, see the listing in Figure 4. This script iterates through all the instances of the specified bolt and, for one or more named bolt surfaces, searches the rest of the assembly for the nearest named surface.

Searching for existing named faces is simpler than finding all the faces separately but it needed me to apply named surfaces on the mating parts, which I did using a plugin that I will talk about in the future. Since I have used a search approach there was no need to have matched name pairs for surfaces, eliminating one of the potential sources of error.

The search method comes from SciPy, which is bundled with ABAQUS, and is heavily adapted from an example I found using AI. The KDTree is a spatial search algorithm that compares two surfaces, defined as sequences of coordinates, and returns distances between points on the surfaces. The surfaces in this case are very loosely defined by extracting the coordinates of the vertices that make up the faces in the surface. It seems to be enough. A running check on the minimum distance is maintained, along with a note of which instance and surface contained it. Once all the instances have been checked a tie is created between the named surface and the minimum distance searched surface. The cleaned-up assembly is shown in Figure 3.

Conclusion

Python scripting in ABAQUS, suitably applied, is a game changer for everyone. At the end of this I have reclaimed hours of productive time, built some reusable code to help out in the future, and achieved a consistent result across the repaired models.

This code can run on arbitrarily large assemblies and could be customised further:

Repair or replace other types of constraints.

Gain more functionality from a simple user interface (coming soon).

Automatically make a copy of the target model in case the repair fails.

To download the example CAE file, Student Edition, and the source code for this example create a user account and click the Download button.

Comments