Post #6 - Scripting More Complex Geometry

- guyrushton9

- Oct 4, 2025

- 7 min read

I am behind on my posting schedule – I might plead that life is getting in the way, and it has been a rotten few weeks, but the truth is that this post took a lot longer than I anticipated to make the code reliable, for reasons that will become clear. The target was to demonstrate a few of the script functions associated with sketching and generating geometry, beyond making very simple geometric shapes. In my book I created a bolt with a thread and a drilled head, because this post was originally for LinkedIn I decided to create a business card holder.

Creating a single variant was relatively simple, if a little tedious, but no one would ever script a one-off solution. Scripting only becomes relevant when you wish to reliably generate whole families of geometries. So, the game was to create a script with a simple user interface which could generate variations on the basic design to suit the user’s taste. Easy. Or not.

Basic Design

The generic design is a tray, with a shaped endcap, that slides inside an outer shell. There are clips set into the side of the tray that latch on to the housing so that the tray cannot be removed once assembled. These clips also form a positive latch when the case is closed. The ends of the box can vary from flat to a generous dome. The upper and lower surfaces of the box likewise and the user can select how much radius to apply to both the vertical corners and the long sides.

User Interface

User interfaces are trouble that is best avoided. However, they are essential in many cases. A full GUI is not necessary in this case. There are two useful text input boxes, one for single values, getInput, and one for multiple inputs, getInputs, that run in the kernel without the overhead of creating a full GUI plugin.

In this case I used the multi-input version. GetInputs only works with text values but it can usefully be wrapped up in a module that checks values and converts data types back to their intended version, see Chapter 6 of Abaqus Scripting Springboard, or blog post #7. For this example I chose not to do that but put all the code to get the user's choices into the function GetDimensions.

Input value control and checking is important, especially if variant generation is going to be automated. The video in this article header was created by pushing through a number of different parameter variants, not all of which were immediately compatible, typically because radiusing the corners caused problems. Debugging the relationship between the corner radius and other parameters to get a successful model was surprisingly awkward. I can strongly recommend not applying radiuses to your models unless they are essential!

Base Geometry

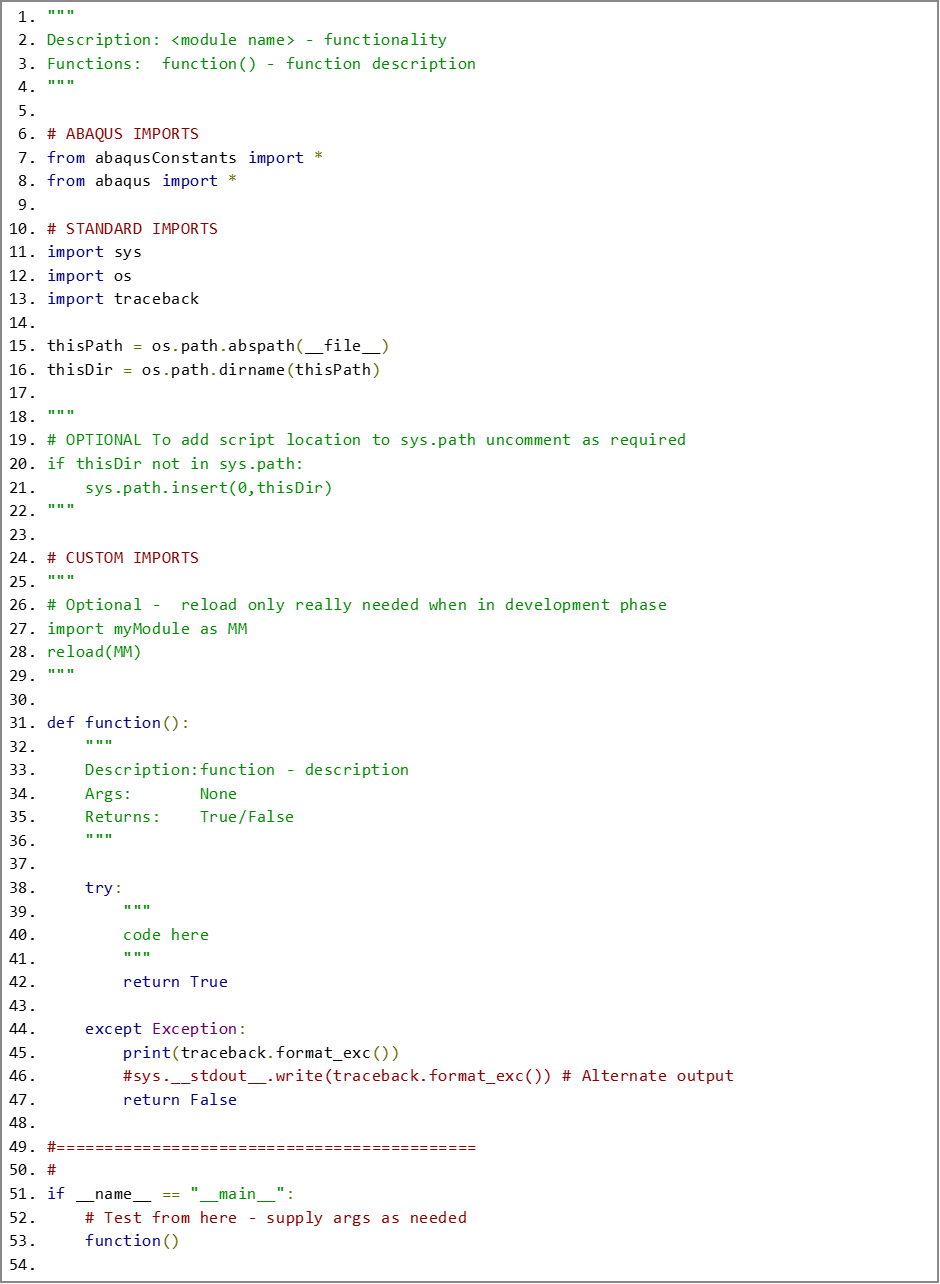

Every model starts with a base geometry. This is the first extrusion, revolve, etc. In the case of the base extrusion there is no choice about the direction of the extrusion. The sketch is always on the XY plane and it always extrudes along positive Z. A special variant of the part’s extrude function is used as shown:

In this case, to make creating an assembly easier, I chose to start both part models from the same plane, where the lid and the case meet to close the box, and to use global coordinates. Doing this meant that instancing the parts without offset automatically created a correct assembly.

In general, I do not recommend doing this. For two main reasons:

Making all the parts extend in the same direction makes the geometry easier to keep track of. Assembling the parts via named surfaces etc is not particularly onerous.

One of the parts first extrusion would be in the ‘wrong’ direction and had to be removed later. This constraint can force odd decisions in your modelling which make life more difficult later. In this case a piece of the tray’s cap was extruded to provide a base, which did not matter since it had to be hollowed out in any case.

Expanding Geometry

Once you have a base piece you need to add to it by defining more sketches on planes of your choosing. There are multiple ways to define a new plane. In this case I chose the simplest which is offsets from the standard planes. A reference vertical is also required, again in this case I used one of the standard axes in the sketching plane.

Once you have a plane defined, the sketch needs to be aligned to it so that it is on the plane. This is done via the transform matrix, which takes the plane and reference direction and rotates the sketch appropriately. Notice that the base sketch did not need this and cannot accept a transform. Given that many sketches were needed I wrapped the sketch creation step into a separate function:

To keep the coding as simple as possible some thought is required to decide how you build up the form you want. The code below shows how the body of the tray component is built up, with the hole in the bottom to allow the user to push cards up and out of the tray, included in the base part, rather than as a separate feature.

As a further example, the internal ribs for stiffening the casing are made up from just two sketches. The rib sketches do not need to be precise either in length or height because a third extrude cut clears the excess off, via a profile that has a very large square around it. This means that many options can be dealt with easily, since there is no need to calculate the size of the clean-up cut.

Details

Detailing the geometry, adding chamfers and radii is conceptually very simple when you are building by script since, at any given stage, the geometry is basically the same, the same edges appear in the same locations. Except sometimes they do not when you are varying the size of elements. Rather than relying on consistent indexing for features that need extra details, a stronger solution is to use searches, based on knowing where those features should be in space. This allows your geometry to vary considerably and even to have optional elements within it, which would make addressing features by a fixed index impossible. I go into more detail on this in Chapter 17 of ABAQUS Scripting Springboard.

In this case the biggest problem was with the radii. As anyone who uses ABAQUS will know, sometimes the rads just do not work. Quite a lot of experimentation went into finding appropriate limits to the geometry combinations that can be produced so that the script always produces a functionally correct design. It is tempting to put rads and chamfers into the sketches, but I would recommend not doing so. Keeping them as separate features makes them easier to remove or alter and the coding overhead to search is small.

Clips

The clips that hold the tray inside the cover and provide a locking mechanism when closed are simple cantilevers. Snap fits like this should be analysed early on in a design to limit the stress in the material. Because the details are generated on the fly for the full geometry, a second copy can be created to create a standalone model that checks the stress in the clip as it bends. Adding the other parts of a basic model, loads, materials etc is straightforward and the model will run in a few seconds.

Result

After more tinkering than I like to admit, the script generates a very wide range of variants on the core geometry. A complete assembly is produced so that the two parts can be verified. The assumption is made that the model can be exported for 3D printing, so the tolerances are generous and fixed. There is no limit to the detail that you could go into.

The amount of time invested to create this part was more than I expected but I was also designing the part as I wrote the code. It would be much easier if the core design was already completed and a script was being created to generate variants. Scripting geometry, indeed, whole models, becomes more useful when you have product families, or provide a service that requires analysis for customised products. The investment to create the scripts is then paid back very quickly as the model preparation is accelerated.

The animation at the head of this article was generated completely using ABAQUS, again a subject for a future post.

The complete code for this example and other blog posts is available for free by registering as a member of this site and clicking on the download button at the top of this article.

Comments